Kendick Lamar’s Halftime Revolution: A History Lesson in Storytelling

The Overview

To understand Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl LIX halftime performance you should start with The Great Migration. Labor shortages after World War I, combined with poor socioeconomic conditions, farm failures and crop damage, as well as Jim Crow laws led to a mass migration of Black Americans from the South to cities such as Chicago where Kendrick Lamar’s parents came from. People also moved west to cities such as Los Angeles (i.e., Compton) where Lamar was born and raised. For Super Bowl LIX Lamar and his team pgLang returned to the Deep South (Louisiana) where Black American (or just American) music was born.

The Great Migration significantly altered urban and rural populations throughout the United States across multiple generations, and it reshaped numerous Northern urban centers. As a result of the concentration of Black people in a place free of Jim Crow and lynchings, the Great Migration arguably spurred Black political action and the civil rights movement. — Britannica

Social issues followed Black Americans to their new destinations, especially poverty and racism, largely in the form of segregation and carcerality, which refers to a system of punishment and incapacitation to control people. Lamar’s mother Paula convinced his father, who was associated with a Chicago gang, to move to California for a better life. Unfortunately, the promise of a new life in Compton was clouded by gang violence. Black gangs, which formed in the early 1970s, had two federations: the Bloods and the Crips. Lamar grew up around the Westside Piru gang (branched from the OG Crips), but he is not gang affiliated.

Music was a constant presence in Kenny and Paula’s household, exposing Lamar to a diverse range of artists from an early age. The Grammy winner also credits his parents’ contrasting personalities — “my father being a complete realist, just in the streets. And my mother being a dreamer” — for his musical tastes. — Nasha Smith

All of these influences, along with his reverence for the late Tupac Shakur and 1990s hip hop culture, are evident in Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl LIX halftime performance. At the time, there was a lot of pressure on groups such as Public Enemy and N.W.A. to not perform certain songs. Lamar (K-Dot) was certainly aware of this, so let’s break down some of the elements of K-Dot’s halftime performance.

Prelude — “Welcome to the Great American Game”

I get way too petty once you let me do the extras

Pull up on your block, then break it down, we playin’ Tetris…

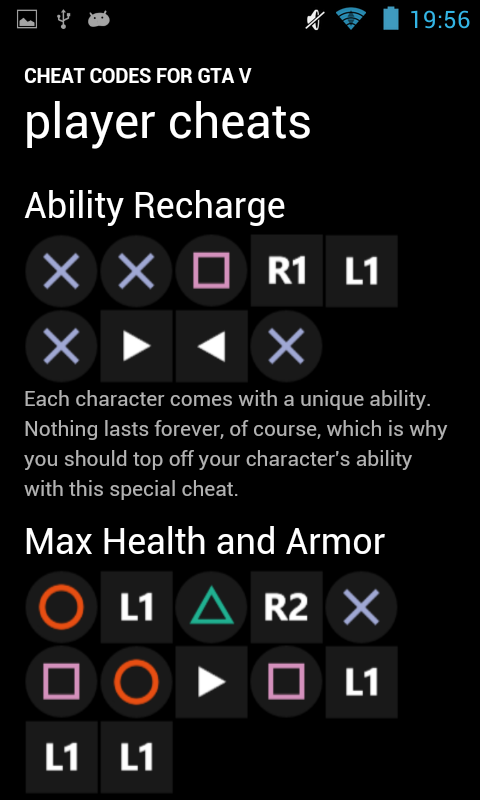

An overarching theme for the halftime show is game theory, a type of interactive decision-making where outcomes for the ‘player’ depends on the actions others. Kendrick Lamar was the primary player while the dancers appeared to move throughout the show as non-playable characters or NPCs in a video game that is not controlled by the player. The show was organized by game levels or sections of a video game that players must complete to achieve an objective.

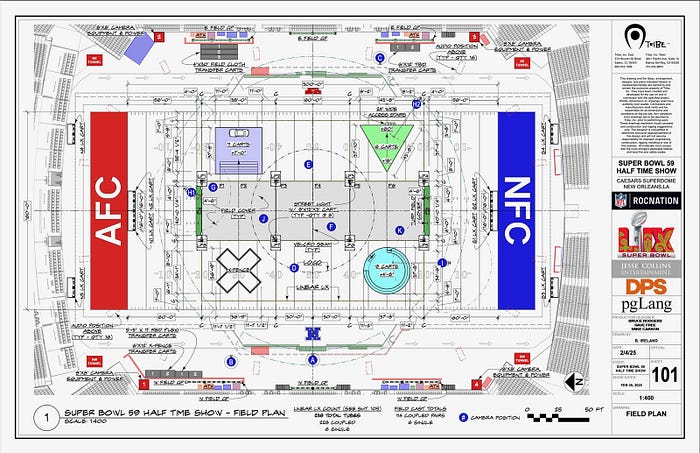

A “Wacced Out Murals” instrumental backed the first appearance of Uncle Sam(uel) L. Jackson who welcomed us into the “Great American Game.” One person wrote on Twitter, “PlayStation buttons as the 4 main stages. Uncle Sam narrating the game.” “Absolute cinema,” added another. Before viewers, on our screens appeared a giant PlayStation controller with the triangle, circle, cross, and square buttons; and a prison yard/neighborhood block that ran horizontally across the middle.

Right on cue, as Lamar rapped his way through “Bodies,” the car that Eastland found and gutted popped open to reveal a small army of dancers. It highlighted just one of four stages Lamar used during the halftime show. Each performance space was shaped like a button on a PlayStation-style controller, a performance intended to portray Lamar’s life as a video game. — Angela Watercutter, Wired

The show also seemed to pay homage to Squid Game, Netflix’s South Korean dystopian drama series. In the series indebted people are invited to play a series of children’s games for a chance at a large cash prize. Instead of green sweatsuits from the ‘TV’ show, the halftime performers wore red, white, and blue sweatsuits that are the colors of the U.S. flag and, alternately, two colors (red and blue) representing the Bloods and Crips.

The ‘Trojan horse’ is a powerful myth that has endured for thousands of years. It first appeared in Homer’s Iliad, which tells of the end of the Trojan War. It represents something that is intended to defeat or subvert from within usually by deceptive means. A Trojan horse also refers to malware that misleads users of its true intent by disguising itself as a normal program. In the Super Bowl LIX halftime show, the dancers emerge from the GNX as a Trojan horse. The GNX was released in 1987, the year Lamar was born. It was a ‘sleeper car’ that beat the top Ferrari race car, a car the rapper Drake is known for owning. Also, founder Enzo Ferrari was nicknamed “iL Drake.”

Introduction — “Doing What I Want to Do”

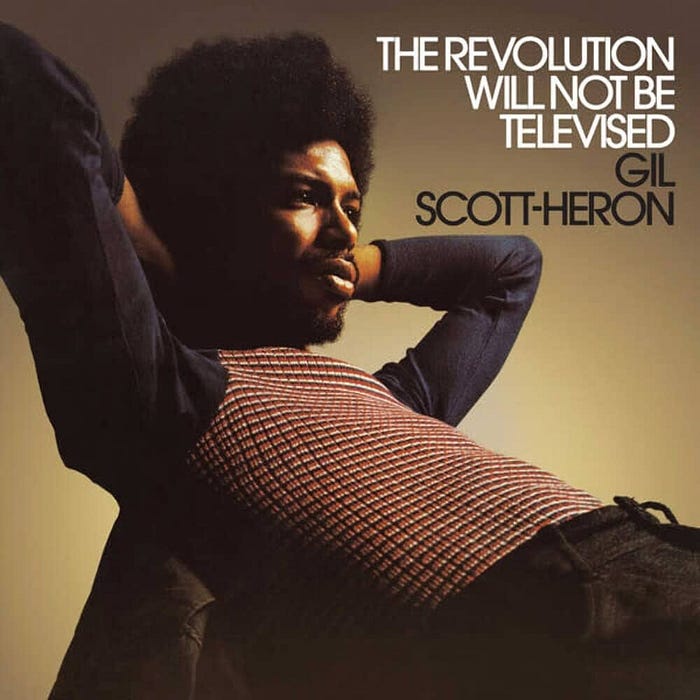

At the top of the show Kendrick Lamar squatted on the hood of a Buick GNX that is also featured on the cover of his most recent album of the same name. As he rapped, he bounced and swung his left arm like an NPC. After “Bodies” Lamar said, “The revolution is about to be televised / you picked the right time but the wrong guy,” as he jumped down from the car. Here, he referenced Gil Scott-Heron’s song “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” which tells people that they can’t be passive participants in the ‘revolution’. Scott-Heron’s song foreshadowed the development of hip-hop and, most likely, Lamar grew up learning about the time period when it was created (the Black Panther Party originated in Oakland, CA).

When the revolution happens, you’re going to have to be in the streets. If you want to make change in society, you have to get off your ass and take action.

Next, Lamar and his dancers performed the song “Squabble Up.” Uncle Sam(uel) was not pleased. He replied that the performance was “too loud, too reckless, too ghetto.” Sam tells Lamar to tighten up to play the game.

Level 1—” It’s Time to Play the Game”

It’s levels to it, you and I know

B*tch, be humble (Hold up, b*tch)

Sit down (Hold up, lil’ — hold up, lil’ b*tch)

Level 1 of the halftime ‘game’ took place atop a square button, as a shortcut for context-sensitive information. Lamar performed “Humble,” a popular song that recently sold 20M units and is eligible for double diamond status. The rapper stood between two sections of male dancers who were arranged by colors to create the U.S. flag. Lamar’s placement divided the human ‘flag’ representing a divided nation. This performance had a lot of patriotic imagery while underneath it pointed a finger at the U.S. and it’s past that was built on the free labor (backs) of Black bodies and its current status (i.e., anti-DEI, anti-woke). Lamar stood alone while the others bowed to the current regime, possibly paying homage to August Landmesser, a German man who appeared in a 1936 photograph (possibly) conspicuously refusing to perform the Nazi salute (see Elon Musk).

Lamar transitioned to “DNA” which pleased Uncle Sam(uel), who by then, was revealed to represent the ‘establishment’ and their usual expectations for performers doing a Super Bowl halftime show. Sam is content with bigger hits and the spectacle but a sign can be seen in the crowd that says, “Wrong Way.” This is not where the rapper wants to stay in the game.

“A Cultural Cheat Code”

Lamar pivots and performs “Euphoria,”which is a diss track the rapper wrote in response to rapper Drake’s “Push Ups” and “Taylor Made Freestyle.” “Euphoria” takes its name from a TV drama executive produced by Drake, as well as referencing Kill Bill: Volume 2 in response to the film’s heroine Uma Thurman’s support for Drake in the battle. It should be noted that Lamar performed these songs on what appears to be either a prison yard or a neighborhood block through the middle of the game controller. Lamar is known for using double entendres or multiple meanings in his lyrics and music videos.

Uncle Sam(uel) aka actor Samuel L. Jackson, who represented societal constraints on Black art and protest was the perfect choice for the show considering his activist past. In 1969, he was expelled from Morehouse College for locking board members in a building for two days in protest of the school’s curriculum and governance. Included in this group of people who were held hostage was Martin Luther King Jr.’s father. Jackson was also one of the ushers at MLK Jr.’s funeral.

Keep these bums away from me

Keep my essence contagious, that’s okay with me

I burn this bitch down, don’t you play with me or stay with me

I’m crashin’ out right now, no one’s safe with me

I did it with integrity and these boys still try to hate on me, just wait and see…

For the “Man at the Garden” doo-wop segment Lamar performed at the base of a light pole, with a Hyphy-style Greek chorus accompanying him, which was the rapper’s way of recognizing the Bay area and to provide a collective voice on the action in every scene they appear in (also see “Squabble Up”). Instead of masks the Hyphy chorus wears gold grills. They also represent the ghosts of K-Dot’s ‘dead homies’. During the doo-wop K-Dot asked viewers if they wanted the ‘dangerous me or the famous me?’ Uncle Sam(uel) responds saying that Lamar used a cultural cheat code and told the score keeper to ‘deduct one life’ for pivoting away from the spectacle towards introspection, which is not what the establishment wanted from him. Cheat codes refer to video games where a player can enter a code to gain an advantage or a disadvantage.

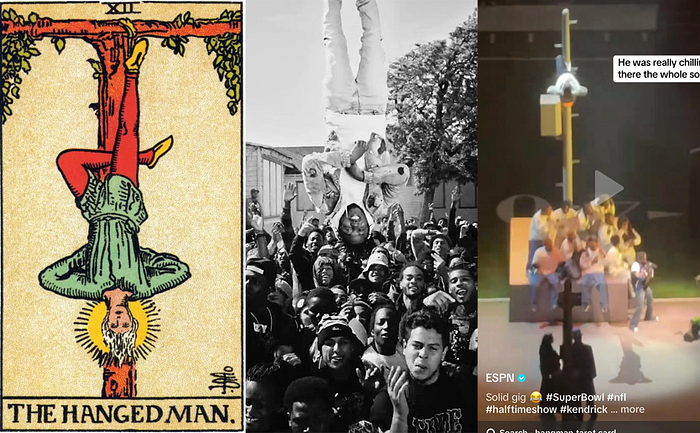

It also should be noted that K-Dot is on top of a street light pole in the “Alright” music video as well. K-Dot is seen hanging upside down. In Tarot , the “Hanged Man” card represents a need to surrender, sacrifice, or let go of something in order to gain a new perspective, often signifying a time to pause, reflect, and embrace change by stepping back from a situation and looking at it differently; it symbolizes the idea of letting go of the ego and trusting the process of transformation.

Level 2— “Teasing A Special Move”

In most PlayStation video games, pressing the X button makes your character jump and for “Peekaboo” Lamar and his dancers appeared to bounce and jump around. Rumor has it that hidden in this song/performance is a conspiracy involving the death of rapper XXXTentacion who was featured in another song by Juice WRLD with the same title. Then, he teased “Not Like Us” before performing “Luther” and “All the Stars” with SZA.

Levels 3 & 4 — “Give Them What They Want”

On the PlayStation the circle button is sometimes used for canceling a move, while the triangle button represents viewpoint or direction. On these mini-stages Lamar performed (with SZA) songs that are considered to be more ‘pop’ than hip hop, which gave the rapper a much needed breather while satisfying Uncle Sam(uel) who praised Lamar for ‘giving America what it wanted’. What was implied here was that American mass culture prefers simpler, catchy melodies over more complex rhythms, with prominent rapping and storytelling that draws from social commentary and personal experiences.

Leveling Up — “Playing The Special Move”

The feel of it is Black America, Free said of Lamar’s show. What does Black America look like, and how to control that narrative of what it means to be Black in America versus the world’s perspective of that is. — Dave Free (WSJ.com)

Uncle Sam(uel) cautions Lamar one last time but is cut short by Lamar finally performing “Not Like Us”, the 5-time GRAMMY-winning diss track written amidst his highly publicized feud with Canadian rapper Drake. According to rapper Open Mike Eagle, “NLU” is the “most successful, scathing, scandalous, dance-floor ready diss song we’ve ever heard in hip hop history.” While he teased “Not Like Us” for a second time Lamar says: 40 acres and a mule / this is bigger than the music. Here, he referenced an unfinished Reconstruction-era “revolution,” that serves as a stand-in for the period’s ill-fated promises (i.e., reparations) and unfulfilled potential.

This part of the performance told viewers that the promise (of a better life) was never truly fulfilled, thus, “40 acres and a mule” (reparations) and the “cultural divide” is still plaguing the U.S. This did not please Uncle Sam(uel) who exclaimed that Lamar had lost his ‘damned mind’.

Lastly, the halftime dancers didn’t just dance. They marched, evoking discipline and uniformity while wearing red, white and blue. Serena Williams who was once fined for ‘Crip walking’ at Wimbledon got her payback on the football field. This was Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl call-to-action in the face of an increasingly far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political movement in the U.S. Lamar ended the 13-minute journey with “TV Off” and perhaps pointing back to his earlier Gil Scott-Heron reference he turned the game/TV off by clicking an invisible remote control as he turned and walked away (with a smile). Once again, the revolution may or may not be televised but it definitely was HEARD.

The performance ends with ‘Game Over’ because this is how Lamar lets us know that he beat the game. He defied the establishment’s ‘rules.’

Yeah they tried to rig the game but you can’t fake influence.